When 31-year-old Sherilee Sharko took the ice, I didn’t notice anything different about her.

During warm up I sized up the opposing team of ladies from the other end of the rink and noted Sharko’s speed. We will have to watch that one, I thought to myself.

At centre ice, facing off in Ponoka — a small farming town located 45 minutes south of Edmonton, Alberta — my initial deduction was that Sharko was likely adjusting her equipment underneath her bright yellow jersey, the sleeve appearing empty.

It wasn’t until she stick-handled around me, passing the puck to her teammate, that I understood she was playing hockey with one arm.

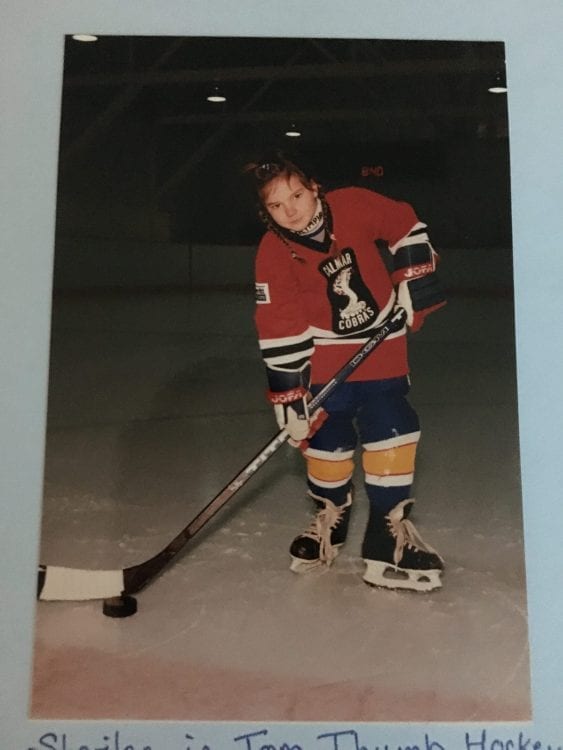

Hockey was always a part of Sharko’s life. Starting at the age of four, and guided closely by her hockey fanatic Dad, Sharko, who works on the family farm that sits between Devon and Calmar, about a 50-minute drive southwest of Edmonton, lived and breathed the game.

Honing her hockey skills, she played in various leagues, mostly on AA boys and men’s teams, and attended numerous hockey schools from Grade 6 until high school graduation. Some of the schools were at least an hour drive each way from the family farm.

At 14, she even took the ice with her dad Randy’s beer league team, an additional opportunity on the ice for the forward who set her sights on playing for Team Alberta, or even playing for Team Canada.

“I played all over the place. I had really dedicated parents; my dad would sell a kidney to have us play hockey,” Sharko said, speaking over the roar of a busy harvesting combine she’s driving.

At age 16, the forward, known for bodychecking boys twice her size, took to the ice with the Edmonton Chimos, a semi-professional women’s hockey team in the Western Women’s Hockey League. In 2012 the Chimos were combined with other teams to form Team Alberta, which is now based out of Calgary and Edmonton for western Canadian elite female players.

As it goes with any competitive sport, especially hockey, Sharko wasn’t offered a spot after tryouts with Team Alberta, and was cut from the Chimos after playing on the team for only a year.

Not wanting to reduce herself to essentially what would be high level rec-leagues at 19, Sharko hopped on the 20-hour plane ride to her mother’s home country of Australia.

With her dual Canadian-Australian citizenship, farming background, family connections and wanderlust, she planned on getting a job, and with her hockey equipment in tow, had loose ideas to tryout for an elite Australian ladies hockey team. That never happened.

Only six months into her time in Australia, Sharko took up work for a distant acquaintance at a cattle farm near Munglinup — a southwestern Australian community with a little over 100 people. It has a gas station and little else.

It was here that tragedy struck the 19-year-old. One afternoon Sharko’s jacket was entangled in the unguarded belt drive of a power take-off — a mechanical system which transfers power from a tractor — and she was dragged onto the drive unit of the tractor, severing her right arm.

The employer pleaded guilty to Failing to Provide and Maintain a Safe Work Environment, a failure that would forever alter the life of a 19-year-old with hopes of continuing her hockey career.

After eight weeks of hospitalization and aggressive rehabilitation in Australia, she returned to the family farm in Alberta to learn how to eventually take over the farm for Randy.

It wasn’t until many years later, on a makeshift outdoor rink constructed by her boyfriend, Mitch, whom she met in Australia, that hockey returned to Sharko’s life.

“We would just go out there everyday, skate, and mess around with the puck. I would splat the puck around and it was all kinds of frustrating,” she says.

She practiced this way, teaching herself through trial and error, when her neighbour suggested that she play on a ladies recreational hockey team in Devon — a farming town situated 26 kms southwest of Edmonton with close to 7,000 people.

Pushing the puck around with Mitch was one thing, but organized hockey, with even a minuscule amount of competitiveness, was a different bag.

“I told Mitch, ‘You need to make me go;’ it was an extremely nerve-racking feeling,” Sharko says.

It was only Sharko’s second organized hockey game since her accident 12 years ago when I met her on the ice. Her speed was an advantage when a minor break-away resulted in a goal she snuck past our goalie. And, as in years past, her dad was the first person she called.

“I was like a little kid at 31, saying, ‘Dad, I scored.”’

Feeling excited about hockey again Sharko took to the Internet to see if she could find someone who could make her a prosthetic arm specially for playing hockey. She was referred to Dan McKinnon, a certified prosthetist at Prosthetics and Orthotics Care Company in Edmonton, AB.

McKinnon says hockey prosthetics are relatively rare. He says that 85 per cent of amputees are diabetic or elderly, and most live sedentary lifestyles. Only 11 per cent of the population are traumatic amputees, and even less are upper extremities, such as the transhumeral amputation (an amputation between the shoulder and elbow), which Sharko has. Those percentages are even lower taking into account few wish to play hockey.

McKinnon explains that the custom durable prosthesis, made up of silicon, fibre glass, and other composite materials, will be “bomb proof.”

“I just hope she has a lot more control and effective use of the stick,” McKinnon says. “Once she has two points of contact on the stick she will have significantly more power.”

With the process of casting the prosthetic, creating a custom liner, building an appropriate socket, and fabricating, evaluating, and refining, Sharko is hoping to use her hockey prosthetic next season. The possibility that she will have a well-made hockey prosthetic is a welcomed surprise, considering she and Mitch were thinking about “Frankenstein-ing something together” with her old prosthesis she never wears.

In the meantime, she will continue playing with one arm, grateful she has returned to the game she has loved her whole life.

She feels lucky to have found her way back to the sport.

For her it’s more than a game, it’s more than a sport. It’s the feeling of a lopsided, over-sized equipment bag barring down on your shoulder as you trundle through a foot of snow. It’s the feeling when you enter the arena and can hear hockey pucks ricocheting off the boards. It’s the camaraderie of a team that shares the “pull up your bootstraps” mentality, like Sharko.

And once she has learned how to use her new hockey prosthetic, she will return to the ice a fearsome predator, just like the underwater creature that shares her name.

DO YOU WANT TO SHARE YOUR HOCKEY STORY?

SUBMIT IT TO WHL PEOPLE HERE!

[adrotate group=”1″]

Related Articles

Categories

Recent Posts

[adrotate group=”2″]